Turning the LRLs into L.O.L.s

An Audiovisual Experience of Parsimonious Voice Leading and Neo-Riemannian Theory in 21st-Century Hollywood Fiction

Chromatic Humor and Audiovisual Narrativity

Parsimonious progressions unfold a spectrum of distinct, narrative connotations. For the purposes of this paper, chromatic functions will be proved as extreme hyperbolic components for expression. Scholars point to these semitonal shifts as a conduit for the “uncanny” (Forrest 2017), building “villain”-like archetypes (Gaf 2023) or even deriving “composite theory” of character transformation and narrativity (Powell 2018). A new trend in Hollywood scoring prompts this interlaced analysis of transformational harmony towards music and humor. Recently maturing its nature in early 21st century Hollywood fiction, LRL transformations now have comedic applications to the overall audiovisual experience. Intersecting Lehman’s (2018) associativity of Neo-Riemannian transformations in audiovisual analysis and narrativity with analytical reviews and representations of humoristic intent by Dynel et al. (2016), this reconceptualization of traditional Neapolitan functions amplify humor and contribute to the narrative structure of comedic scenes in modern film scoring. This paper contrasts historical uses of these LRL transformations to their modern implementations in comedic scenes of 21st-century Hollywood literature to find out to what extent their chromatic nature contributes to the success of the overall narrativity in audiovisual experiences, so that readers can understand the humorous capabilities of semitonal shifts in film music.

Since the early 17th century, perceptual escalations of harmony by semitonal shifts have featured the Neapolitan chord and have contributed greatly to the methodical conceptualizations of emotionally charged and exclamatory musical material. From the Phrygian mode, Neapolitan applications contain a versatile character of chromatic and pre-dominant functions. As Hutchinson (2017) states, the chord’s alteration of texture, register, and dynamics often prompt its definitive sonic characteristic, as seen in the first movement of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7, Op. 92, Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata, John Williams’ Raiders March, Michael Giacchino’s Star Trek Main Theme, and Hans Zimmer and Antonius Tom Holkenborg’s The Red Capes are Coming. The chord’s half-step relation to tonic provokes a strikingly unexpected response, and although its common approach by first inversion allows for pre-dominant function, the semitonal shift in its root position creates a subversion of expectations which prove to enhance the overall listening experience.

Initial writings from Lewin (1982) formalized these transformations into what later became expanded upon as Neo-Riemannian theory. Disassociations from modality provided a clean slate of analysis for versatile projections of hermeneutic interpretation, as will be used for the topic of this paper. Semitonal triadic movements void of traditional functioning progressions allow for active speculation, measuring chromatic correlations within the perceived intent of a clear and conclusive narrative. It is important to make a certain distinction for the sake of this research: both the Neapolitan chord and the bVI-V resolution will be stripped of their tonal functions for this analysis. Only the utilization of its Neo-Riemannian analysis between these shared LRL transformations will be observed. The audiovisual narrativity discussed here is more so related to the semitonal shifts of the film score for storytelling purposes, rather than its traditional harmony.

Emotional Origins of the Neapolitan Chord

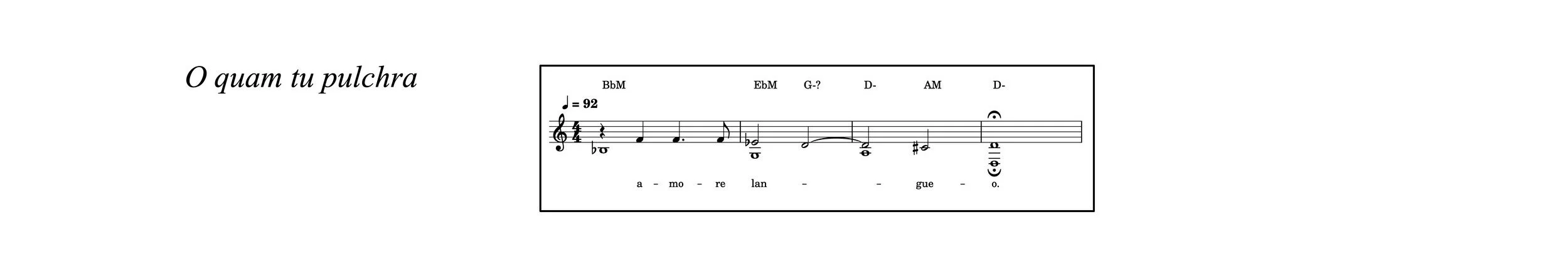

A brief survey of the Neapolitan-equivalent to LRL transformations leads one to Early Baroque music. Experimentation with chromatic functions at this time provided a richness and greater expression of the pre-dominant chord, opening possibilities for more creative and emotionally charged material that served the text. Later coined by English composer and theorist William Crotch in his 1812 book Elements of Musical Composition, he refers to the Neapolitan chord as part of the collective “geographical chords”. Used mostly in minor keys, its corresponding melodies have from this time outlined heart-felt feeling and outward turmoil. Its earliest notated example can be found in Alessandro Grandi’s O quam tu pulchra es (1625), where his musical material is mostly sweet in context but contrasts with the second appearance of its words “for I languish with love”, which is accompanied by the implied Neapolitan-functioning Eb major chord (see Example 1.) As a compilation of verses from the Song of Songs, its lovely nature is shifted appropriately for the word “languish”, evoking an intense emotional entanglement to this chromatic moment.

Example 1.

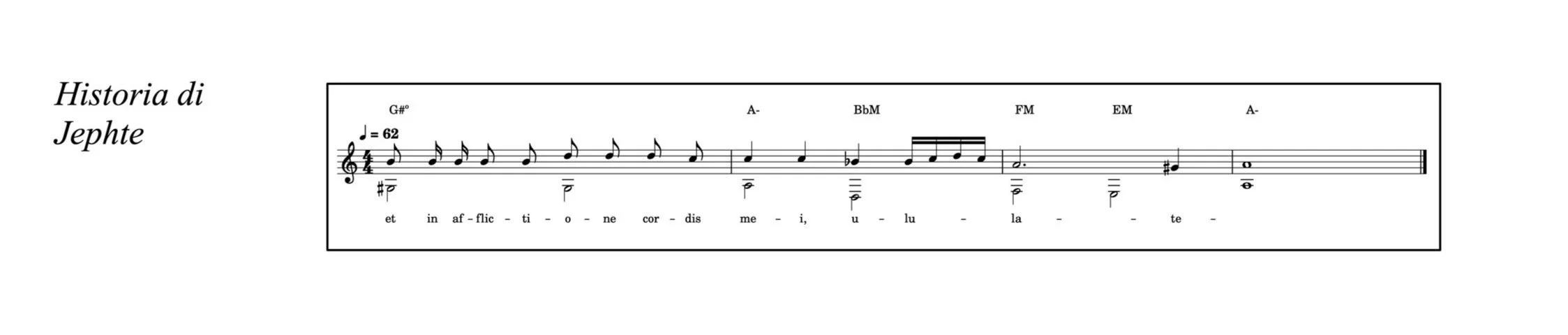

Similar to Giacomo Carissimi’s Historia di Jephte (1648), a clearer example of the earliest usage of the Neapolitan chord is exuded multiple times throughout the lament of Jephte’s daughter (see Example 2.). In this context, the daughter sings in realization after she finds out she was promised as a sacrifice by her father to God. This narrative further elaborates the emotional association of this chord’s (Bb major) purpose, even in its earliest, contrapuntal form.

Example 2.

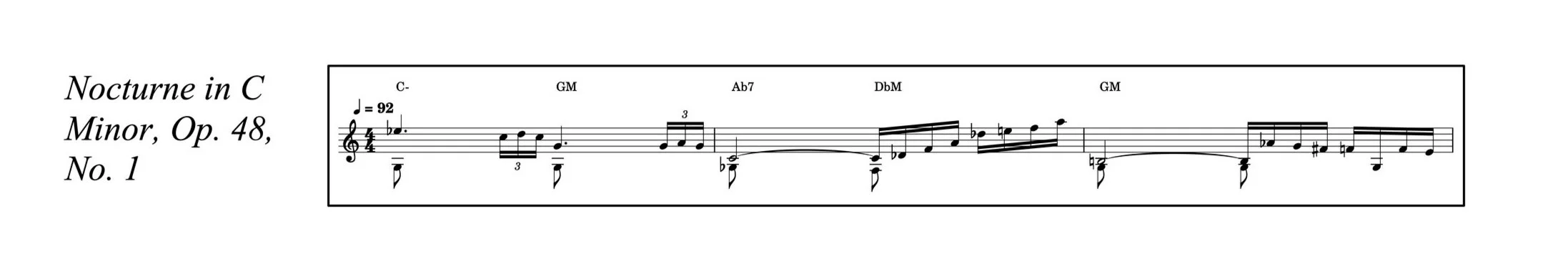

In a different vein, the final cadential phrase of Chopin’s Nocturne in C Minor, Op. 48, No. 1 (1842) subverts expectations, employing the Neapolitan chord Db major through a deceptive resolution of an authentic cadence (see Example 3.). This moment ramps up the intensity of the climax through an elongation of its harmonic rhythm, sustaining loud dynamics, and inching further from while simultaneously closer to what we expect to be the climatic ending of this composition. While this popular example of chromaticism empowers this same great feeling of grief, other applications such as frequent Neapolitan functions and overall chromatic narrativity in the form of Gustav Mahler’s Ninth Symphony, as stated by Patterson (2011), contributes to a holistically different musical interpretation, depicting the descent from life to death.

Example 3.

LRL as Non-Verbal Humor Cue

Concerning its iterations in 21st century Hollywood audiovisual experiences, the reconceptualization of the Neapolitan chordal function as a “musical jester” evokes dramatic, over-the-top characteristics which enhances distinctly comedic and humorous scenes. In tandem, the prosody of nonverbals (Attardo et al. 2011) in film scenes strengthen this lens of film scoring, which amplify humorous effects. Utilizing its corresponding Neo-Riemannian analysis, there are noticeable correlations between LRL transformations (including its variants: PLRL/LRLP, and frequent PL) and dramatic intent in various scenes’ “comedic punch”. While not every LRL transformation performs in this hyperbolic experience, when the transformations are used instantaneously alongside quintessential “humor cues” (Dynel et al 2016), its clear associations with highly laughable moments cannot go unnoticed. Nuanced examples of these LRL transformations in popular movie-humorous scenes as an expansion on humor and narrative are analyzed here, as scenes presented in this paper uncover the prime examples of these chromatic musical events through overall storytelling.

The “Musical Jester” in Action: Case Studies

Despicable Me – The Minions’ Sonic Signature

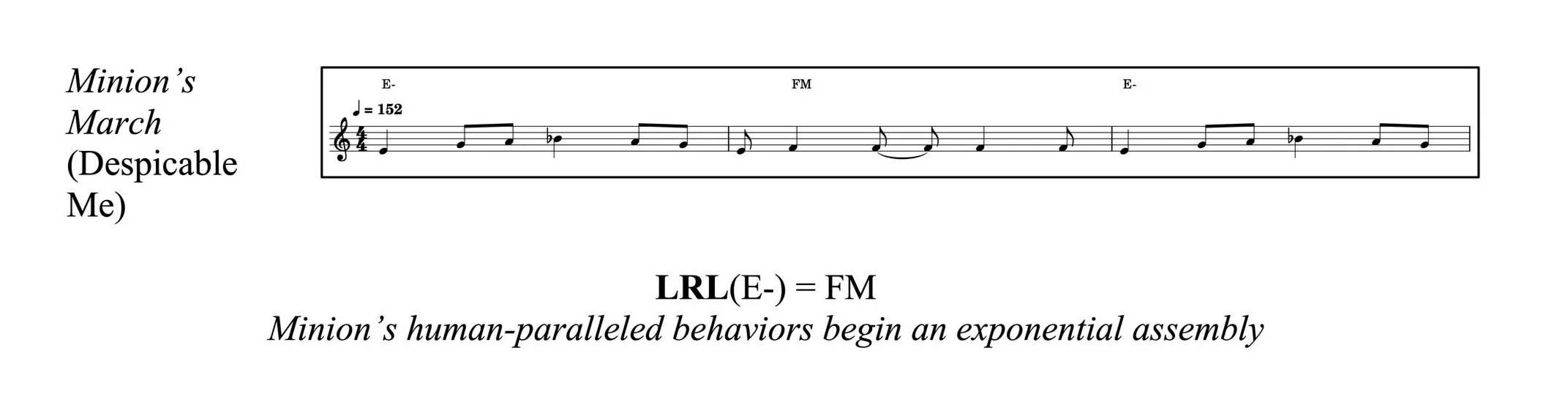

In the 2010 crime, comedy animated film Despicable Me, the LRL transformation is embedded into the character theme of the loveable and sporadically unhinged Minion (see Example 4.). A monumental scene, the minions’ first introduction to the big screen is exponential, as their musical counterpart Minion’s March repeats in hyperbolic fashion as human-like tasks are carried out by these goggle-eyed yellow mutants. Above all else, the entire correlation of the minion to comedy is lost without realizing its singular unique aspect of their nature that is wholistically cherished by every adult and young child: their audacious form of communication. This scene, which “assembles the minions”, contains syncopated LRL transformations at every instance where the minions are seen communicating to and responding with each other regarding Gru’s order of assembly.

Example 4.

This assimilation of bombastic sophistications from the minions introduce the viewer to the nonsensical, as their hyperbolic and human-like gestures seen here are known to define the minion’s archetype through the entire film. This moment is consequently amplified by the “musical jester” of the LRL transformation. In response to Gru’s initial order “Minions, assemble!”, the first close-up angle of two minions working to construct a support beam serves as the basis for this scene’s exponential nature. Upon hearing Gru’s call-to-assemble, one of the two minions rushes the count on securing a screw, resulting in the hammer smashing against the minion’s head before sliding down a fire-fighter-like poll to alert the others of Gru’s order. This sequence contains the first occurrence in the film of this LRL transformation, coinciding directly with the streams of senseless communication from these minions revealed to the audience. Their excessive body language and sporadic nature in speech is amplified by these non-verbal cues, equally exaggerated by the musical material saturated in the “musical jester”.

This instance of the LRL transformation pops dramatically from the pre-existing texture of the film score, which contained stable ostinatos, a funky bass groove, and various percussive syncopations, entraining the listener to a simple, quadruple meter. The first sentence of the minion sliding down the poll explodes with this LRL transformation, suddenly unifying its texture and presenting a completely different musical gesture. This highlights the key moment of this audiovisual experience, clearly introducing the nature of the minions’ communication to the audience. From E minor to F major, with slight modulations throughout, these LRL transformation’s resolve back to its originating triad, presumably due narratively to the exponential dissemination of information from minion to minion regarding Gru’s order. This pattern continues in increasing fashion until a wide shot of the entire minions assembling is achieved. The tangibleness of these minions’ noises and clumsiness have been acknowledged as universal signs of humor, conveyed in their sweet, naïve, and generally goofy nature. The existence of the LRL transformation integrated into the very essence of this theme should not go unnoticed, as the utilization of its timing and texture supports the function of these semitonal shifts as the “musical jester”.

Ant-Man – A Superhero’s Hyperbolic Theme

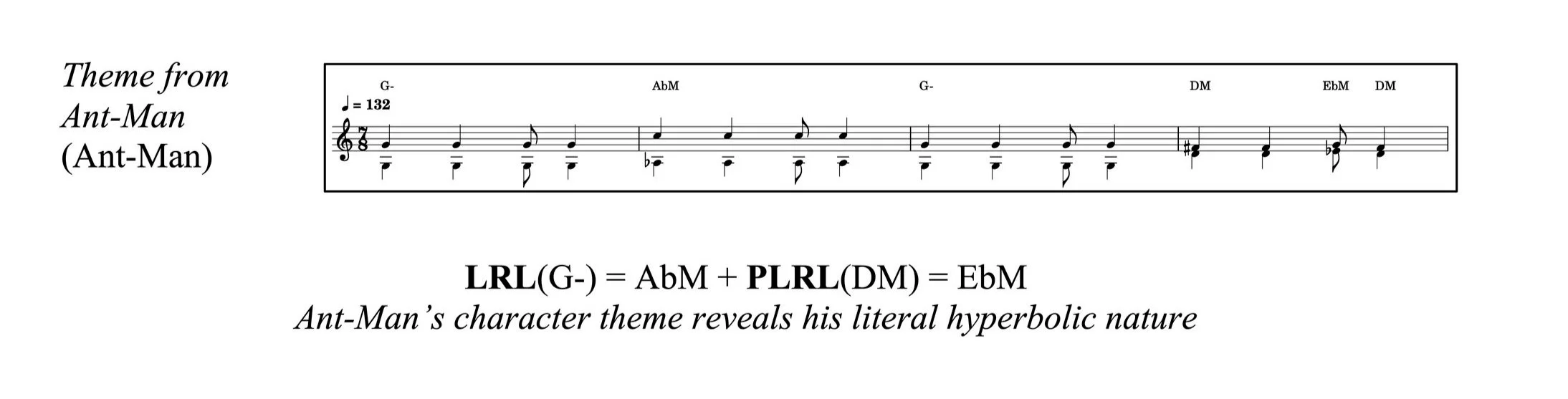

This employment of texture and LRL transformations as non-verbal cues to enhance the humorous frame is not dissimilar to other popular crime, comedy films. Another movie entry, Ant-Man (2015), conveys a similar adaptation of these LRL transformations (see Example 5.).

Example 5.

While providing emphasis to the more humorous, dry, and witty traits of this character, Ant-Man is also quite literally hyperbolic in its ability to transform distances between atoms and shrink and grow at will; its character theme is no different. Sly dynamic swells and clever 7/8 grooves boast a unified texture of syncopated and very distinct LRL transformations. From G minor to Ab major (LRL), and D major to Eb major (PLRL), these brass-heavy rhythms and over-the-top spy-quirks create an environment of intrigue and drama, rivaling even the most iconic character themes of the current-standing Marvel Cinematic Universe. As in Minion’s March, these clear textural shifts surrounding the LRL transformation reveal the “musical jester” as loud, exaggerated, and overstated. Such are the actions of Ant-Man throughout the entirety of the film.

In addition, before the end credits roll, there is a scene of Luis explaining his convoluted and overly detailed story regarding information about another potential heist opportunity to Ant-Man. This fast-paced retelling and hyper-stated form of narrativity is to be expected at this point by the audience from this character, since there was a nearly identical scene of the same purpose earlier in the film. The key difference from this scene at the end of the film is that it ultimately falls flat. After Ant-Man and the audience are weaved into this complex storytelling by Luis, he ends his monologue disappointingly. Enacting a notion of failed humor, as stated by Dynel et al. (2016), results in Lui’s intention and the hearer’s interpretation of the speaker’s intention to be not compatible, making the final scene of Ant-Man so frustratingly comedic. As the audience struggles with this elongated and expectation-defying humorous frame, the movie cuts to the end credits and states the character theme of Ant-Man in its most bombastic nature. Riding on the backs of flying ants, slashing jokes from the back of a taco food truck, and saturating dialogue through slapstick comedy, this humor engrosses the movie and is beyond iconic. With the character theme of Ant-Man thoroughly defined through its audacious LRL transformations and overly dramatized orchestral stabs, the emphasis of these semitonal shifts throughout the context of this film is truly substantial.

Encanto – Hypocrisy and Humor in “We Don’t Talk About Bruno”

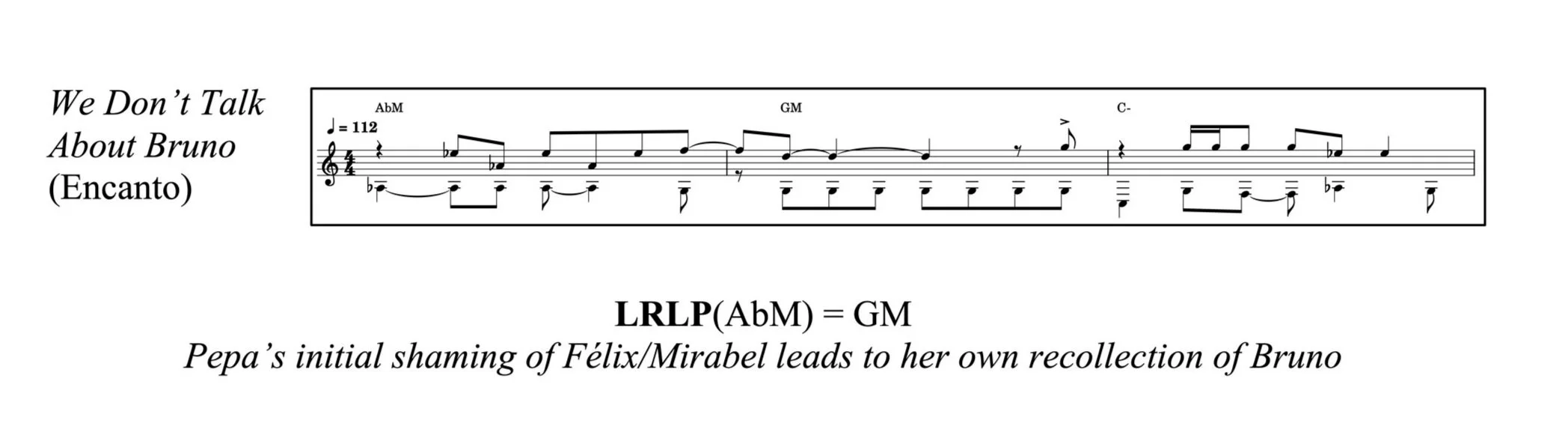

We Don’t Talk About Bruno from Encanto (2021) is a musical hyperbole in its own hypocritical form. The scene begins with Pepa shaming her husband, Félix, and Mirabel for talking about Bruno, and then proceeding to talk about Bruno herself. This action from Pepa is simultaneously greeted by an LRLP transformation from Ab major to G major, and a diatonic walkup to the first chord (see Example 6.). This transformation is then repeated twice, exemplifying the nonverbal cues similar to the “musical jester” from Minion’s March.

Example 6.

While the LRL transformations in Minion’s March are a dissemination of the minion’s goofy communication and sporadic gestures, the entire opening scene of We Don’t Talk About Bruno is instead littered with comedic foreshadowing and dramatizations surrounding countless testimonies about Bruno. Pepa’s actions of shooing away Félix and waving disapproval at Mirabel quickly becomes replaced by the loving embrace of herself and her husband, giving a plethora of nonverbal cues to the true intention of this entire scene. Her husband’s premature offering of his hand to dance through this beginning segment, joining hers, is followed by Pepa’s exclamative "BUT!", revealing that she knew all along what their true intention was: to spew lies about Bruno to Mirabel, despite their initial forewarning.

The usage of the LRL transformation in this context expands the humorous frame by enveloping its turn of events from Pepa and the others as a humorous hypocrisy. The song elaborates a hyperbolic degradation of Bruno by blaming him for saying he “told [them their] fish will die and the next day, dead!”, and “he told [them they’d] grow a gut, and just like he said!”, or even “he said that all [their] hair would disappear, now look at [their] head”, proceeding to rip off their wig, all loosely embodied by abbreviated occurrences of this LRL transformation. The “musical jester” here holds ties to the opening statements of Pepa and the gossip throughout the entire song, making a spectacle of the hypocritical narratives they have against Bruno. These ridiculous arguments and their coinciding “musical jesters” not only hint at the overall narrativity of these characters against Bruno but point to the humorous collective claims made against him, all while they plead “not [to] talk about Bruno”, when the entire song is in fact them talking about Bruno.

The Incredibles – Heroic Irony in “Life’s Incredible Again”

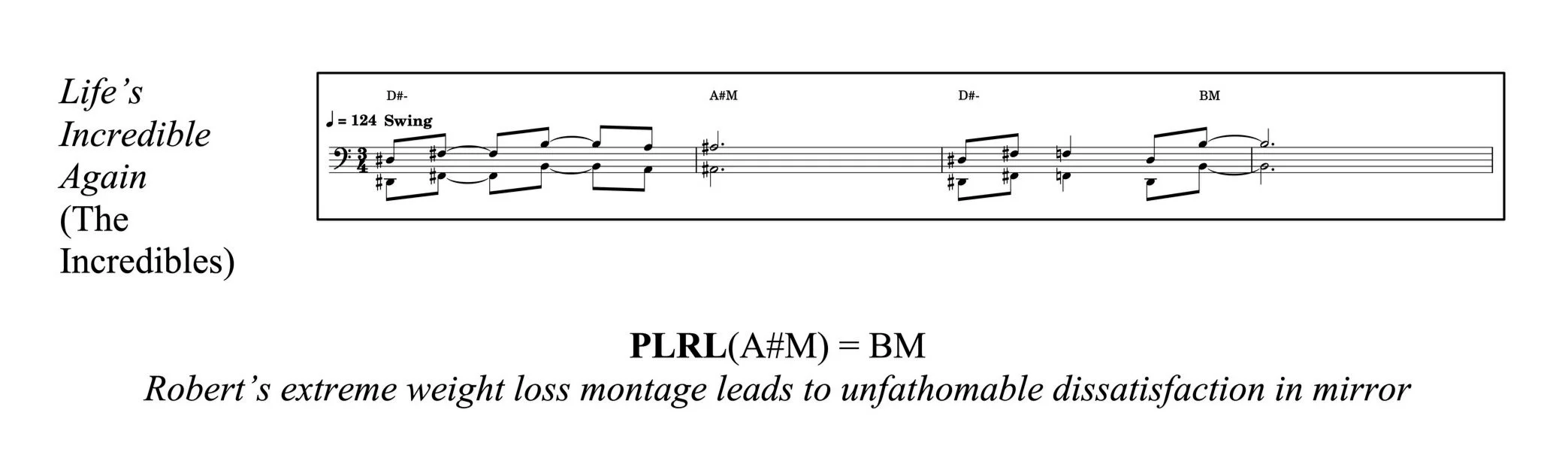

The Incredibles (2004) explores a setting for the traditional American family, but if they were subjugated to the social confines of being “supers”. Life’s Incredible Again elevates this established humorous frame by assisting in the non-verbal cues of a specific moment of disbelief in the physical physique of Mr. Incredible. His assimilation to civilian life, void of hero work, is depicted throughout this scene by jazzy and playful variations of its main theme. Mr. Incredible is shown adopting many stereotypical parental roles in this new life with his family, and there is a particular moment that reveals a surprisingly funny revelation: Mr. Incredible struggles to lose weight.

His whole archetype is based on a hyperbolic narrative of the fatherly figure, so this scene, with all his superpowers and super-human strength, still lacks progress in maintaining shape. This is engrossed in humorous irony. The specific moment that chronologically reveals this conundrum is Mr. Incredible’s evaluation of his physique in the mirror, pulling a huge line of freight cars in a dead sprint, and then returning to the mirror in disappointment upon realizing his physical shape remains unchanged. The montage cuts in the very next scene to Mr. Incredible impulsively reading a magazine entitled “Get In Shape”, ultimately resolving this humorous scene. The brief reveal described here is reflected by textural changes and variations in harmonic rhythm of Life’s Incredible Again, as the perceived inappropriateness of Mr. Incredible’s current state in tandem with the following “musical jester” evokes a compositional effect such as irony (see Example 7.). From A# major to B major, this PLRL transformation is timed perfectly to the before and after of this revelation toward Mr. Incredible. By rhythmic and timbral variations, this brass-heavy texture of the theme provides a supportive and overtly extreme hyperbolic vessel which expresses the irony in this scene via the audiovisual experience. Like the analysis of Theme from Ant-Man, this LRL transformation conveys a humorous frame in tandem to the overall conventional plot of their respective films, as this flaw from Mr. Incredible turns into multiple humorous gags throughout the entire movie.

Example 7.

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban – The Ascension of Aunt Marge

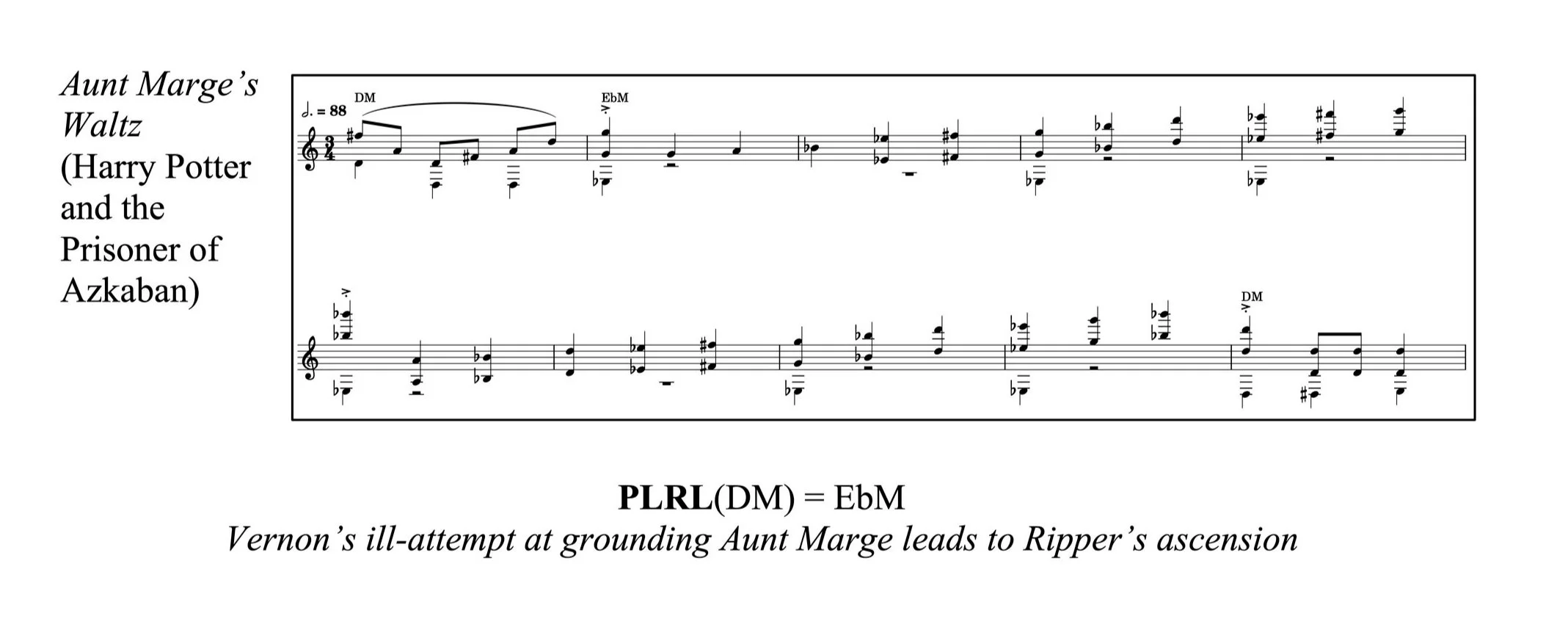

Finally, Aunt Marge’s Waltz from Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2004) enriches this act of turning LRL’s into L.O.L.’s in the film music from 21st century Hollywood fiction in spectacular fashion. Vernon’s ill-attempt at grounding Aunt Marge is a memorable scene from the installments of the Harry Potter franchise, and the magic from Harry Potter becomes acquainted with one of the first emergences of this “musical jester”. A nonsensical spectacle, Aunt Marge is slowly but surely pulled upwards by gravity in ridiculous fashion. Vernon tries holding her limbs to the ground, but he too is soon dragged against the ground and lifted into the air. In this scene, even Vernon’s dog attempts to weigh the two of them downwards, but as the three desperately attempt to return to the earth below, an LRL transformation suspends this predicament in a wide shot that prompts a giggle from the audience (see Example 8.). Sitting on a semitonal shift from D major to Eb major (PLRL), this fictional act is not only reflected in the upward ascension of Aunt Marge, Vernon, and his dog, but of the melodic content itself.

Example 8.

The “comedic punch” in this audiovisual experience is from the humorous frame of the plot, the literal ascension of harmony through this triadic shift, and the directional tremolo upwards from the violin melody as this LRL transformation halts this tricky predicament of Aunt Marge in space and time. Even the music itself cannot seem to resist this ascension, as even the tonal center briefly modulates upwards via the “musical jester”. Tapping into the ludicrous progression of events in this scene, chromatic alterations prime the audience for what is ultimately a beyond fictional endeavor. As Powell (2018) states, the film music becomes an equal contributor in the explication of the narrative within the self-contained entity of the film.

Conclusion: Turning LRLs into L.O.L.s

This, by its analysis, argues that the LRL transformation is utilized as an additional non-verbal humor cue, signaling the enhancement of various humorous frames. As Dynel et al (2016) points out, these humor cues can increase an avoidance of failed humor and minimize the risk of misunderstanding and miscommunication on the hearer’s part, or in some cases, as found in the research of this paper, harness the nature of its duality. Non-verbal humor cues such as prosody, laughter, and canned (audience) laughter are used to heighten the reception of comedic intent, and now with this correlation of revitalized LRL transformations in this context, the humorous frame is further demarcated and clearly solidified through this component of the audiovisual experience. Implications of this chromatic material in recent film scenes have deconstructed Neapolitan functions from tragic and emotionally charged vessels to personified “musical jesters”.

Utilizing transformational analysis to correlate occurrences not with its function within a tonal key, but to the impact on the audiovisual experience, the emergence of these LRL shifts in humorous movie scenes have been found to enhance both the spectacle and the hysterical. These specific semitonal shifts now embody a completely humoristic role, with LRL transformations adding the “comedic punch” to the audiovisual experience. Through an analysis of nuanced application, evolution, humor cues, and musical hermeneutics, this trend has thus been extrapolated upon and serves to enhance the research of future film scores in and beyond the context of humorous audiovisual experience in 21st century Hollywood fiction.

Bibliography

Attardo, Salvatore. Manuela Maria Wagner, and Eduardo Urios-Aparisi, eds. Prosody and Humor. Pragmatics & Cognition 19, no. 2 (2011): 1-246.

Bourne, Janet. “Perceiving Irony in Music: The Problem in Beethoven’s String Quartets.” Music Theory Online 22, no. 3 (September 1, 2016).

Chung, Andrew Jay. “Lewinian Transformations, Transformations of Transformations, Musical Hermeneutics,” January 1, 2012.

Crotch, William. Elements of Musical Composition : Comprehending the Rules of Thorough Bass, and the Theory of Tuning. London : Printed for Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, & Brown by Nathaniel Bliss, Oxford, 1812.

Dynel, Marta, Alexander Brock, and Henri de Jongste. “A Burgeoning Field of Research: Humorous Intent in Interaction.” Journal of Pragmatics 95 (April 1, 2016): 51–57.

Forrest, David L. “PL Voice Leading and the Uncanny in Pop Music.” Music Theory Online 23, no. 4 (December 1, 2017).

Graf, Benjamin. Turning to the "dark side" of John Williams: Towards a Theory of the Villian Texas Society for Music Theory 45th Annual Meeting, 2023.

Hirsch, Lily. Taking Funny Music Seriously. Indiana University Press. 2024.

Hutchinson, Robert. Music Theory for the 21st-Century Classroom, 2017.

Lehman, Frank. Hollywood Harmony: Musical Wonder and the Sound of Cinema. Oxford Music/Media Ser. Oxford: Oxford University Press USA - OSO, 2018

Lehman, Frank. “Reading Tonality Through Film: Transformation Theory and the Music of Hollywood (Dissertation),” May 1, 2012.

Lewin, David. “A Formal Theory of Generalized Tonal Functions.” Journal of Music Theory 26, no. 1 (1982): 23–60.

Mirka, Danuta. “The Oxford Handbook of Topic Theory,” 2014.

Powell, Andrew. “A Composite Theory of Transformations and Narrativity for the Music of Danny Elfman in the Films of Tim Burton,” May 31, 2018.

Patterson, Jason. “The Adagio of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony: A Schenkerian Analysis and Examination of the Farewell Story,” 2011.

Principi, Dylan. “Rethinking Topic Theory: An Essay on the Recent History of a Music Theory.” Music Theory Online 30, no. 1 (March 1, 2024).